Usage

Tidy Evaluation with rlang Cheatsheet Tidy Evaluation (Tidy Eval) is a framework for doing non-standard evaluation in R that makes it easier to program with tidyverse functions. Non-standard evaluation, better thought of as “delayed evaluation,” lets you capture a user’s R code to run later in a new environment or against a new data frame. R recognizes 600 time zones. Each encodes the time zone, Daylight Savings Time, and historical calendar variations for an area. R assigns one time zone per vector. Use the UTC time zone to avoid Daylight Savings. OlsonNames Returns a list of valid time zone names. OlsonNames withtz(time, tzone = ') Get the same date-time in a new. The tidyverse is a powerful collection of R packages that you can use for data science. They are designed to help you to transform and visualize data. All packages within this collection share an underlying philosophy and common APIs.

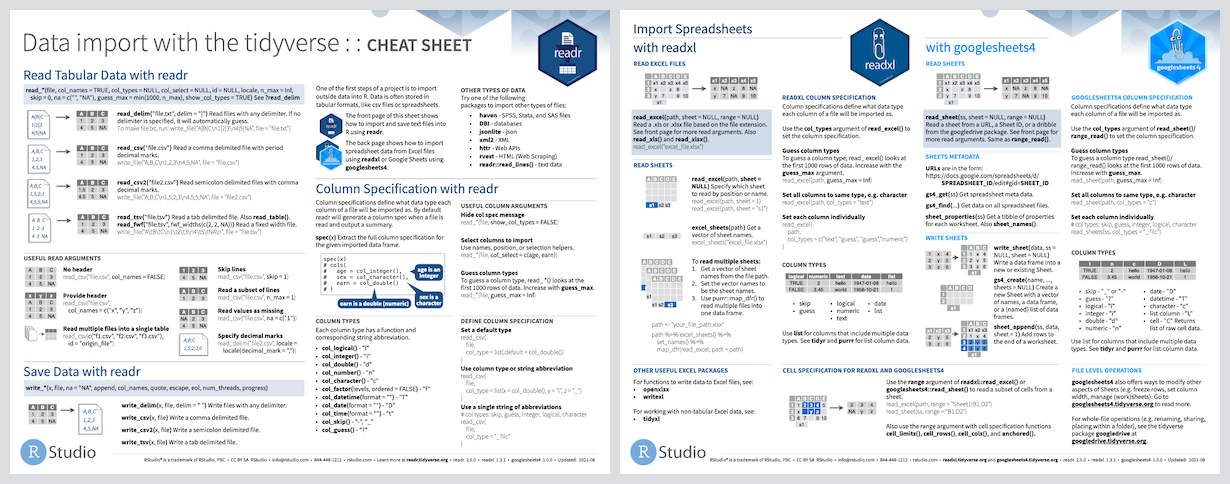

readr is part of the core tidyverse, so load it with:

- R Syntax Comparison:: CHEAT SHEET Even within one syntax, there are o'en variations that are equally valid. As a case study, let’s look at the ggplot2 syntax. Ggplot2 is the plotting package that lives within the tidyverse. If you read down this column, all the code here produces the same graphic. Quickplot ggplot.

- Tools to help to create tidy data, where each column is a variable, each row is an observation, and each cell contains a single value. Tidyr contains tools for changing the shape (pivoting) and hierarchy (nesting and unnesting) of a dataset, turning deeply nested lists into rectangular data frames (rectangling), and extracting values out of string columns. It also includes tools for working.

To accurately read a rectangular dataset with readr you combine two pieces: a function that parses the overall file, and a column specification. The column specification describes how each column should be converted from a character vector to the most appropriate data type, and in most cases it’s not necessary because readr will guess it for you automatically.

readr supports seven file formats with seven read_ functions:

read_csv(): comma separated (CSV) filesread_tsv(): tab separated filesread_delim(): general delimited filesread_fwf(): fixed width filesread_table(): tabular files where columns are separated by white-space.read_log(): web log files

In many cases, these functions will just work: you supply the path to a file and you get a tibble back. The following example loads a sample file bundled with readr:

Note that readr prints the column specification. This is useful because it allows you to check that the columns have been read in as you expect, and if they haven’t, you can easily copy and paste into a new call:

vignette('readr') gives more detail on how readr guesses the column types, how you can override the defaults, and provides some useful tools for debugging parsing problems.

vignettes/dbplyr.RmdAs well as working with local in-memory data stored in data frames, dplyr also works with remote on-disk data stored in databases. This is particularly useful in two scenarios:

Your data is already in a database.

You have so much data that it does not all fit into memory simultaneously and you need to use some external storage engine.

(If your data fits in memory there is no advantage to putting it in a database: it will only be slower and more frustrating.)

This vignette focuses on the first scenario because it’s the most common. If you’re using R to do data analysis inside a company, most of the data you need probably already lives in a database (it’s just a matter of figuring out which one!). However, you will learn how to load data in to a local database in order to demonstrate dplyr’s database tools. At the end, I’ll also give you a few pointers if you do need to set up your own database.

Getting started

R Tidyverse Cheat Sheet Pdf

To use databases with dplyr you need to first install dbplyr:

You’ll also need to install a DBI backend package. The DBI package provides a common interface that allows dplyr to work with many different databases using the same code. DBI is automatically installed with dbplyr, but you need to install a specific backend for the database that you want to connect to.

Five commonly used backends are:

RMariaDB connects to MySQL and MariaDB

RPostgres connects to Postgres and Redshift.

RSQLite embeds a SQLite database.

odbc connects to many commercial databases via the open database connectivity protocol.

bigrquery connects to Google’s BigQuery.

If the database you need to connect to is not listed here, you’ll need to do some investigation (i.e. googling) yourself.

In this vignette, we’re going to use the RSQLite backend which is automatically installed when you install dbplyr. SQLite is a great way to get started with databases because it’s completely embedded inside an R package. Unlike most other systems, you don’t need to setup a separate database server. SQLite is great for demos, but is surprisingly powerful, and with a little practice you can use it to easily work with many gigabytes of data.

Connecting to the database

To work with a database in dplyr, you must first connect to it, using DBI::dbConnect(). We’re not going to go into the details of the DBI package here, but it’s the foundation upon which dbplyr is built. You’ll need to learn more about if you need to do things to the database that are beyond the scope of dplyr.

The arguments to DBI::dbConnect() vary from database to database, but the first argument is always the database backend. It’s RSQLite::SQLite() for RSQLite, RMariaDB::MariaDB() for RMariaDB, RPostgres::Postgres() for RPostgres, odbc::odbc() for odbc, and bigrquery::bigquery() for BigQuery. SQLite only needs one other argument: the path to the database. Here we use the special string ':memory:' which causes SQLite to make a temporary in-memory database.

Most existing databases don’t live in a file, but instead live on another server. That means in real-life that your code will look more like this:

(If you’re not using RStudio, you’ll need some other way to securely retrieve your password. You should never record it in your analysis scripts or type it into the console. Securing Credentials provides some best practices.)

Our temporary database has no data in it, so we’ll start by copying over nycflights13::flights using the convenient copy_to() function. This is a quick and dirty way of getting data into a database and is useful primarily for demos and other small jobs.

As you can see, the copy_to() operation has an additional argument that allows you to supply indexes for the table. Here we set up indexes that will allow us to quickly process the data by day, carrier, plane, and destination. Creating the right indices is key to good database performance, but is unfortunately beyond the scope of this article.

Now that we’ve copied the data, we can use tbl() to take a reference to it:

When you print it out, you’ll notice that it mostly looks like a regular tibble:

The main difference is that you can see that it’s a remote source in a SQLite database.

Generating queries

To interact with a database you usually use SQL, the Structured Query Language. SQL is over 40 years old, and is used by pretty much every database in existence. The goal of dbplyr is to automatically generate SQL for you so that you’re not forced to use it. However, SQL is a very large language and dbplyr doesn’t do everything. It focusses on SELECT statements, the SQL you write most often as an analyst.

Most of the time you don’t need to know anything about SQL, and you can continue to use the dplyr verbs that you’re already familiar with:

However, in the long-run, I highly recommend you at least learn the basics of SQL. It’s a valuable skill for any data scientist, and it will help you debug problems if you run into problems with dplyr’s automatic translation. If you’re completely new to SQL you might start with this codeacademy tutorial. If you have some familiarity with SQL and you’d like to learn more, I found how indexes work in SQLite and 10 easy steps to a complete understanding of SQL to be particularly helpful.

The most important difference between ordinary data frames and remote database queries is that your R code is translated into SQL and executed in the database on the remote server, not in R on your local machine. When working with databases, dplyr tries to be as lazy as possible:

It never pulls data into R unless you explicitly ask for it.

It delays doing any work until the last possible moment: it collects together everything you want to do and then sends it to the database in one step.

For example, take the following code:

Surprisingly, this sequence of operations never touches the database. It’s not until you ask for the data (e.g. by printing tailnum_delay) that dplyr generates the SQL and requests the results from the database. Even then it tries to do as little work as possible and only pulls down a few rows.

Behind the scenes, dplyr is translating your R code into SQL. You can see the SQL it’s generating with show_query():

If you’re familiar with SQL, this probably isn’t exactly what you’d write by hand, but it does the job. You can learn more about the SQL translation in vignette('translation-verb') and vignette('translation-function').

Typically, you’ll iterate a few times before you figure out what data you need from the database. Once you’ve figured it out, use collect() to pull all the data down into a local tibble:

collect() requires that database does some work, so it may take a long time to complete. Otherwise, dplyr tries to prevent you from accidentally performing expensive query operations:

Because there’s generally no way to determine how many rows a query will return unless you actually run it,

nrow()is alwaysNA.Because you can’t find the last few rows without executing the whole query, you can’t use

tail().

You can also ask the database how it plans to execute the query with explain(). The output is database dependent, and can be esoteric, but learning a bit about it can be very useful because it helps you understand if the database can execute the query efficiently, or if you need to create new indices.

R Tidyverse Cheat Sheet Pdf

Creating your own database

If you don’t already have a database, here’s some advice from my experiences setting up and running all of them. SQLite is by far the easiest to get started with. PostgreSQL is not too much harder to use and has a wide range of built-in functions. In my opinion, you shouldn’t bother with MySQL/MariaDB: it’s a pain to set up, the documentation is subpar, and it’s less featureful than Postgres. Google BigQuery might be a good fit if you have very large data, or if you’re willing to pay (a small amount of) money to someone who’ll look after your database.

All of these databases follow a client-server model - a computer that connects to the database and the computer that is running the database (the two may be one and the same but usually isn’t). Getting one of these databases up and running is beyond the scope of this article, but there are plenty of tutorials available on the web.

MySQL/MariaDB

In terms of functionality, MySQL lies somewhere between SQLite and PostgreSQL. It provides a wider range of built-in functions. It gained support for window functions in 2018.

R Tidyverse Cheat Sheet Pdf

PostgreSQL

PostgreSQL is a considerably more powerful database than SQLite. It has a much wider range of built-in functions, and is generally a more featureful database.

BigQuery

BigQuery is a hosted database server provided by Google. To connect, you need to provide your project, dataset and optionally a project for billing (if billing for project isn’t enabled).

It provides a similar set of functions to Postgres and is designed specifically for analytic workflows. Because it’s a hosted solution, there’s no setup involved, but if you have a lot of data, getting it to Google can be an ordeal (especially because upload support from R is not great currently). (If you have lots of data, you can ship hard drives!)